The universality factor is not one limited to Buddhism. Followers of every religion see aspects or images of their faith in everyday situations, culture, literature, and sometimes even tortillas and cinnamon buns. These “sightings” often end up telling us more about ourselves than about the religion, i.e. seeing the beauty of a blooming flower as evidence of a supreme being’s love of beauty or that we truly bask in the wonder that God would take time out of his busy daily schedule to manipulate the heating elements in toasters to create vaguely Jesus-shaped burn marks on bread.

But what is most telling about such visions is that we want to believe. We want to believe that the words of our gospels, hymns, pujas, mantras, and prayers apply to our lives in a fundamental and thinly veiled manner. This is natural and to be expected if we are ever going to push ourselves through toward heaven or enlightenment. Unfortunately, this expectation has to potential to limit our spiritual vision. If we only look for what is obvious as a sign that we are on the right track, we miss out on the infinite subtleties of the Universe. An outsider may not understand the spiritual significance of a Native American peyote ritual or a sweat house, simply because Jesus didn’t talk about it. Or someone may not understand the simple antiquated existence of Mennonites because they live in a metropolis and can’t imagine not having a Facebook account.

In my Dashboard Buddha entries, I will chronicle my attempts to lay the template of my beliefs over commonplace things. It could be any number of sci-fi fandoms, a weekend activity, a movie, a book, a TV show, or a single act of a person that struck me as an enlightened thing to do. I’ll make a concerted effort to turn my spiritual gaze toward the ubiquitous and the unintentionally profound. As George Clooney once said in O Brother, Where Art Thou?, I will “see the lilies of the goddamned field.”

I christen this column with a piece about that most famously misunderstood and deeply geeky of sci-fi adventures: Dune.

I must not fear.

Fear is the mind-killer.

Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration.

I will face my fear.

I will permit it to pass over me and through me.

And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path.

Where the fear has gone there will be nothing.

Only I will remain.

--Bene Gesserit Litany Against Fear, "Dune," Frank Herbert

I’m probably one of the few people who saw the original 1984 David Lynch film version of Dune and was positively mesmerized instead of utterly dismayed. I only saw it because I had been watching Twin Peaks re-runs and had a crush on Kyle MacLachlan and I did what any self-respecting teenage girl does when she has an actor infatuation: I watched everything I could find no matter the known quality or lack thereof. What resulted was affection more powerful than that between a girl and her Hollywood boyfriend. The world of Dune had been unleashed upon my impressionable, youthful sci-fi nerd brain and I was dutifully impressed.

When my dad told me I should read the book I was wholly gobsmacked. “There’s a book?! I must read this book!”

Soon after I started reading Dune, I had the privilege to be retroactively disappointed in David Lynch’s movie. This is the complete opposite experience for most people who love Dune. I believe my example proves more the undeniable genius of Frank Herbert than any backwardness on my part.

Dune, which is richly saturated in all manner of religious allusions, has become an exceptionally abundant goldmine for me. The flakes of Buddhism are shiny and plain to see.

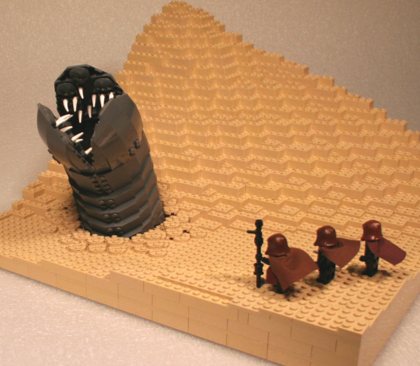

At the beginning of the novel, Paul Atreides, the son of the Duke of Caladan, must undergo a special test. It’s a test that will help determine if he is the Kwisatz Haderach—a prophesied messiah in the “Duniverse” who is said to have the power to bridge time and space and inherit the memories of all his ancestors. The test, which involves placing your hand into a black box and feeling it burn with incredible unbearable pain, is designed to test one’s ability to see through fear, and therefore determine your human-ness (as opposed to “a machine created in the likeness of the human mind”—the ultimate sin). The box itself is nothing more than a box, but through “nerve induction,” you are made to believe that your hand is burning up inside.

During the test, Paul repeats the Litany Against Fear over and over in his mind and passes the test, never jerking his hand out of the box because he realizes that his fear is unfounded. He is the first male in history to pass this test, which makes the Bene Gesserit suspect that he is the Kwisatz Haderach.

The fear Paul experiences is just an altered perception of reality. Buddhism suggests that all of reality is perception. The key concept of the Diamond Sutra—so-called because it cuts through illusion as sharply as a diamond—is that nothing is what it seems.

The Diamond Sutra invokes the example of a rose. What is a “rose?” It’s made up of thorns, petals, a stem, water, chlorophyll, some perfume. But each of these things alone is not a “rose.” That object we call “rose” is actually an amalgam of parts that constitute a “rose.” Just as we are not fully ourselves without our body parts and a soul or an ego and the people who surround us and call us by our name, a “person” is a combination of things. Nothing, except perhaps subatomic particles—and we can’t even be sure of that—is independent of other things.

We meditate upon this and discover a simple, yet weighty philosophical equation: a “rose” is a “rose” because it is not a “rose.” That’s Buddhist math for you.

Fig. 4 Kyle MacLachlan IS the Messiah because he is NOT the messiah... especially if he can't beat up Sting

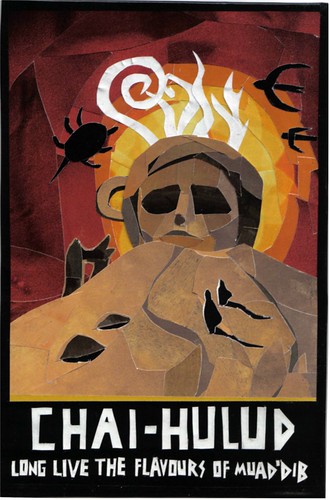

A through-line theme of Dune is that the mahdi “Messiah” or “God-Emperor” involved is not simply a messiah or a god-emperor. Frank Herbert writes of “a world being the sum of many things.” The prescience and “other memory” of all the messiah’s past ancestors makes the messiah everything and everyone, dependent on everything and everyone. Muad’dib is Muad’dib because he is not Muad’Dib.

Muad’Dib, being the wise and prophetic man he is, would have agreed with Buddha implicitly: “There exists no separation between gods and men, one blends softly casual into the other.”

The preceding essay is in no way exhaustive of Dune’s spiritual ore. I promise it will surface again and again in the future, like a tea leaf stirring around and around, up and down in a hot teapot. Mmm spice tea...

I’m probably one of the few people who saw the original 1984 David Lynch film version of Dune and was positively mesmerized instead of utterly dismayed. I only saw it because I had been watching Twin Peaks re-runs and had a crush on Kyle MacLachlan and I did what any self-respecting teenage girl does when she has an actor infatuation: I watched everything I could find no matter the known quality or lack thereof. What resulted was affection more powerful than that between a girl and her Hollywood boyfriend. The world of Dune had been unleashed upon my impressionable, youthful sci-fi nerd brain and I was dutifully impressed.

When my dad told me I should read the book I was wholly gobsmacked. “There’s a book?! I must read this book!”

Soon after I started reading Dune, I had the privilege to be retroactively disappointed in David Lynch’s movie. This is the complete opposite experience for most people who love Dune. I believe my example proves more the undeniable genius of Frank Herbert than any backwardness on my part.

Dune, which is richly saturated in all manner of religious allusions, has become an exceptionally abundant goldmine for me. The flakes of Buddhism are shiny and plain to see.

At the beginning of the novel, Paul Atreides, the son of the Duke of Caladan, must undergo a special test. It’s a test that will help determine if he is the Kwisatz Haderach—a prophesied messiah in the “Duniverse” who is said to have the power to bridge time and space and inherit the memories of all his ancestors. The test, which involves placing your hand into a black box and feeling it burn with incredible unbearable pain, is designed to test one’s ability to see through fear, and therefore determine your human-ness (as opposed to “a machine created in the likeness of the human mind”—the ultimate sin). The box itself is nothing more than a box, but through “nerve induction,” you are made to believe that your hand is burning up inside.

During the test, Paul repeats the Litany Against Fear over and over in his mind and passes the test, never jerking his hand out of the box because he realizes that his fear is unfounded. He is the first male in history to pass this test, which makes the Bene Gesserit suspect that he is the Kwisatz Haderach.

The fear Paul experiences is just an altered perception of reality. Buddhism suggests that all of reality is perception. The key concept of the Diamond Sutra—so-called because it cuts through illusion as sharply as a diamond—is that nothing is what it seems.

Fig. 3 The Diamond Sutra is the Buddha's best friend

The Diamond Sutra invokes the example of a rose. What is a “rose?” It’s made up of thorns, petals, a stem, water, chlorophyll, some perfume. But each of these things alone is not a “rose.” That object we call “rose” is actually an amalgam of parts that constitute a “rose.” Just as we are not fully ourselves without our body parts and a soul or an ego and the people who surround us and call us by our name, a “person” is a combination of things. Nothing, except perhaps subatomic particles—and we can’t even be sure of that—is independent of other things.

We meditate upon this and discover a simple, yet weighty philosophical equation: a “rose” is a “rose” because it is not a “rose.” That’s Buddhist math for you.

Fig. 4 Kyle MacLachlan IS the Messiah because he is NOT the messiah... especially if he can't beat up Sting

A through-line theme of Dune is that the mahdi “Messiah” or “God-Emperor” involved is not simply a messiah or a god-emperor. Frank Herbert writes of “a world being the sum of many things.” The prescience and “other memory” of all the messiah’s past ancestors makes the messiah everything and everyone, dependent on everything and everyone. Muad’dib is Muad’dib because he is not Muad’Dib.

Muad’Dib, being the wise and prophetic man he is, would have agreed with Buddha implicitly: “There exists no separation between gods and men, one blends softly casual into the other.”

The preceding essay is in no way exhaustive of Dune’s spiritual ore. I promise it will surface again and again in the future, like a tea leaf stirring around and around, up and down in a hot teapot. Mmm spice tea...

No comments:

Post a Comment

You're welcome to comment. Just keep in mind this is a personal as well as an academic blog and I like to see thoughtful, respectful commentary. No offensive language or curt replies, please :)