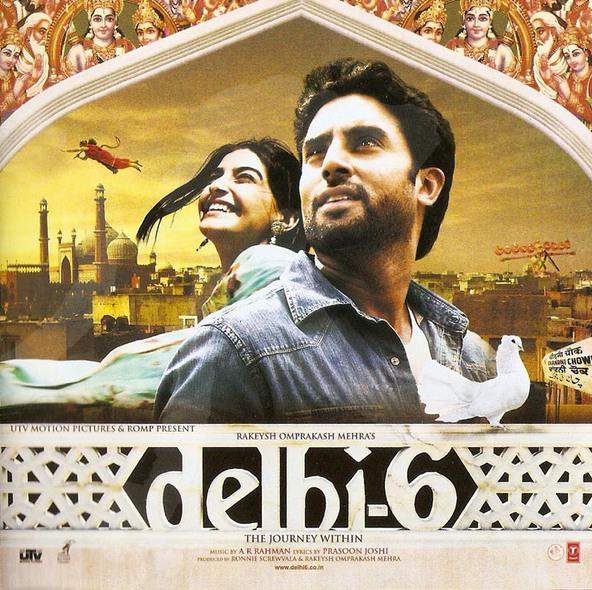

-Abhishek Bachchan in “Delhi 6”

Fig1. If you watch one nontraditional Bollywood movie, watch this one

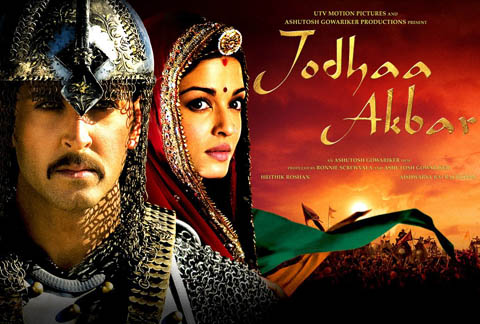

Ashutosh Gowariker’s sweeping historical epic Jodhaa Akbar dramatizes the true story of the Mughal Empire in the 16th century—a period when Islam was spreading well into South Asia under the rule of the Emperor Akbar (“great” in Arabic). The Emperor marries a beautiful and fiery Indian princess in order to quell the belligerance of the Rajput people and cement his role as the ruler of Northern India. One of the central tensions of the film is fueled by the fact that Akbar, a Muslim, and Jodhaa, a Hindu, fall in love despite their traditional differences. Their mutual respect for one another’s faiths and values leads to Akbar’s reputation for generosity and religious tolerance during his rule.

The 2008 film Thoda Pyaar, Thoda Magic is an almost Disney-style family film about an angel who gets sent by God to earth to watch over a family of orphaned children. The main characters, four children of varying ages, are visiting Los Angeles with their new foster father. When a tragedy befalls them, they turn to the most available “temple” in town: a Christian church. When they enter to pray for help, one child wonders if it’s okay to pray there, since they are Hindus. Another child offhandedly remarks that whether it’s Jesus, Vishnu, Ganesha—it’s all the same, insinuating that their prayers will be heard by God no matter where they are.

One of the orphans—adopted by the previous parents—wears a traditional headwrap, identifying him as a Sikh. At one point in the film, he laments the fact that he is a Sikh, because the other children at school bully him. His foster father cheers him up, explaining how important it is to be a Sikh, pointing out their reputation for having great courage.

Fig2. Possibly the most beautiful epic you'll ever see

The popular Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi is set in Amritsar, where the Sikhs built the famous Golden Temple. That many people of varying religions are allowed to worship there is testament to the ideals of Sikhism, which is often described as a hybrid of Hindusim and Islam. Within the film, the main characters—a newlywed couple—go to the temple at plot points when they need to seek understanding and guidance.

In the 1971 film Anand, an Indian Christian nurse prays to Jesus for a patient’s health. When the Hindu patient hears of this, he jokingly frets over whether or not Jesus and Krishna will fight over who gets to help him.

Unlike Hollywood, the folks in Mumbai don’t gag on overt religious themes and trappings within their films. Hindu, Islamic, and Sikh traditions and ideas crop up all the time, which was great for my education. I can site dozens of examples, but most of the prominent religious activities are apparent from the obligatory clichés that are lovingly included in the movies:

1) Weddings: almost always a backdrop or at least a major plot point in the stories of arranged versus love marriages, tradition versus modernization, caste disputes, and feminism.

2) The traditional mother: whether she henpecks, consoles, or encourages her children into whatever choice they make in life, she’s always seen doing household pujas (prayers) or visiting the local temple to implore the Lord’s guidance in family matters--you know, Jewish stuff ;)

3) Holidays and festivals: they may not need an excuse for dancing and partying, but a Diwali, Holi or a Lohri is always exploited for its potential as a big musical number and joyous celebration with lights, bonfires, food, costumes, and colorful powder tossed in the air.

You may say, wait a minute, there are plenty of Hollywood films that show Christian or Jewish ceremonies and holidays that Americans love. We have the great Biblical epics like Ben Hur, The Ten Commandments and The Rope! Look at the sheer volume of Christmas movies out there!

The big difference here is that Christmas movies are rarely about Jesus and the epics are seldom about religious debate. Christmas themes are Christian in origin: peace, rebirth, giving, miracles, etc., but are non-denominational (e.g. The Chronicles of Narnia). In the short-lived TV series Aliens In America (that’s for another blog post entirely!), Raja, the teenage Pakistani exchange student visiting a small town in Wisconsin, wonders aloud why Jesus is so fat in all the Christmas decorations, then realizes, “Oh, that is Santa Claus!”

The epics we know and love are few and far between, and even something like the more recent Kingdom of Heaven (2005), which was severely underrated when initially released, was actually maligned for its deliberative treatment of religion and morality even though it boldly tackled some major religious and political issues that are as relevant today as they were during the crusades. Movies like The DaVinci Code and Passion Of The Christ deal with religion and faith directly, but this happens so rarely in the American film landscape that they attract a disproportionate amount of attention.

Fig.4 The Director's Cut knows best

The “Christian” weddings we see in secular Hollywood movies are set in churches, sure, but they don’t deal with God’s plans for the couple. It’s always about cold feet, whether the bride or groom cheated on each other or if someone is going to break up the wedding.

Explicit religious reflection is not the norm for Hollywood. In Bollywood, it’s standard operating procedure. I am constantly struck by the frequency of religious discussion within Indian films. They are saturated with themes of religious identity, interfaith marriage, karma, destiny, traditions and responsibilities to perform religious rites.

In Bollywood’s version of My Best Friend’s Wedding, all the same American conflicts are included, but there are constant references to how matches are made in heaven, what the Lord has planned for the couple, turning to Hindu astrology to determine an auspicious marriage date, and the main characters are shown praying in front of a shrine dedicated to Krishna in hopes of gaining insight and guidance with all their familial issues.

Sometimes marriage issues aren’t as easily overcome as male rivalries for a woman’s heart. In Yash Chopra’s classic Veer-Zaara, which is based on a true story of a Muslim Pakistani woman falling in love with a Hindu Indian man, deals with the Romeo and Juliet-like theme of forbidden love in modern India, where the politics and emotions created by the Partition of British Colonial India in 1947 still affect people today. Traditional ties between Muslims and Hindus were severely strained by the horrific events of Partition, and the bridging of that religious divide through love and marriage is a common plot point in several Bollywood films.

Fig.5 Who'd have thought Hindu-Muslim relations were so romantic?

The festival scenes always include a song, and the songs incorporate ancient religious imagery or mantras lifted from scripture every time. Characters are constantly shown attending temple services and engaging in prayer. Often the geographical settings, such as Varanasi (Benares), Hrishikesh, and Amritsar, are places of worship and pilgrimage.

One explanation for the prevalence of religious stories and themes in Indian movies is the pluralist nature of Hinduism itself. It is distinguished by its inclusivism, as it has no absolutely unified dogmatic creed. Hinduism was originally an umbrella term for the various religious traditions of India, which included many gods and demi gods or devas. Often villages and towns each adopted their own patron devas, depending on the stories and legends of the geographical area.

In Gowariker’s 2004 film Swades (“Motherland”) the main character visits the town of Charanpur (derived from the word for “feet”), which is so named because it is believed that the Hindu god Ram and his goddess wife Sita left footprints in the hardened mud nearby. Another town up the road may just as easily be named for another deva with an equally sacred and eponymous relic.

Fig.6 An inspiration to return to your roots, and have faith

Recall that in Temple of Doom, Indy and his companions arrive at a small impoverished village whose fate is undeniably linked to the relic of the stolen Shankara stone. The stone is a lingam, a common physical representation of the virility of Shiva. Lingams are indeed believed to be charged with power and strength, but the glowing diamonds inside are a dramatic Hollywood appurtenance.

Sure there are multitudes of devas to keep track of, but Hinduism isn’t technically polytheistic. Every one of the gods and goddesses we’ve heard about have evolved from a single creator god, Brahma, and all are avatars, or differing images, of Brahma. An avatar is like a facet in a diamond—it’s part of the same stone, but seen on a slightly different surface or angle.

It can also be thought of in this way: Think of your mother. You see her as your mother. Your dad sees her as his wife. Her mother sees her as daughter. Her friends see her as a friend. Her brother sees her as sister. Yet she is still the same person. She has many avatars, depending on who sees her, but they are all looking at the same person.

Hindu gods and goddess also have an evolutionary aspect to their existence. Due to the effects of the laws of karma, the avatars of say, Vishnu, appear on Earth at varying periods, each time manifesting as a more wise and powerful and loving being. Vishnu was once a fish (Matsya), a turtle (Kurma), a lion (Narasimha), then the popular human gods of Rama, Krishna, and Buddha. It’s said that when the Earth is polluted and society is corrupt, Vishnu will eventually visit humankind as Kalki and help those souls who lived with good karma in their lives.

With a concept like that, it’s easy to understand why the children in Thoda Pyaar, Thoda Magic believe that even Jesus, who has a comparable role in the Bible’s book of Revelation, can be considered another of Vishnu’s great avatars.

Fig.7 The Ramlila performed in Swades

Bollywood audiences never question or resent this propensity to showcase religious activities because Hinduism and all its interpretations, which have been around for 4,000 years, is sewn right into the fabric of Indian life. It’s always there, and every schoolchild knows the stories of Rama defeating Ravana to rescue Sita, the tale of Ganesha obtaining his elephant head, and how the river Ganges came down to Earth from heaven. Hindu culture is a national tradition, and it influences citizens’ everyday lives whether they’re Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist or Christian.

This doesn’t necessarily lead to peace and harmony, though. People within certain villages or even city blocks worship one deva more than another, or one neighborhood is majority Muslim while the adjacent one is majority Hindu. Identity wars crop up similar to those of street gangs.

Delhi 6 (2009) exemplifies one such conflict. When American-born Roshan travels with his grandmother back to her original home in Delhi, he encounters both Delhi’s deep humanity and superstitious nature first hand. The neighborhood they reside in is being terrorized by the kala bandar (black monkey), some unknown troublemaker that steals goats and sabotages public property. The tension comes to a head, and the Hindus accuse the kala bandar of being a Muslim, and the Muslims accuse it of being a Hindu. They even accuse Roshan of being the monkey because he is an outsider from America. Interfaith friendships are broken and the peace of the community is fractured until the tragic dénouement, and both sides are shamed into learning a hard lesson about living up to the “bigheartedness” of Delhi.

It’s a rich, beautifully constructed film full of complex characters and deep emotional moments that cover the gamut of modern Indian struggles: feminism, generational divisions, arranged marriage, American cultural influences (Indian Idol, anyone?), religious superstition, emerging technology, and national/religious identity. The cameo appearance of Amitabh “Big B” Bachchan as Roshan’s dead grandfather crystallizes the generational theme, since Roshan is played by Amitabh’s real-life son, Abhishek. Anyone familiar with their very celebrated personalities would be especially touched by the significance of the scene they have together. Recall that in Slumdog Millionaire, the young Jamal is so desperate to meet his favorite movie star that he jumps into a river of shit and climbs out just to get his autograph. Who on Earth is worth such a fuss? Amitabh Bachchan. Hands down. The man is his own deva.

Fig.8 Delhi hai mere yaar (Delhi is my friend)

For my birthday one year, my sister, who knows my penchant for studying the world’s gods (movie stars or otherwise), gave me a copy of Sanjay Patel’s “Little Book of Hindu Deities.” All the great gods are in there, and beautifully illustrated in bright crayon colors in an appealing big-eyed-cartoon Hello Kitty style. Each has a one-page summary of their significance and story, but these are intensely simplified from the massive epics of Hindu scripture.

One Hindu epic is the Ramayana, which depicts the journey of Lord Ram’s life story and teaches on how to fulfill life’s duties with virtue and integrity. A major turning point in the story—the abduction of Ram’s wife Sita by the evil Ravana—is portrayed as a play in both Swades and Delhi 6. These plays, or lilas (“divine pastimes”) are often put on during Indian festivals and dramatize the classic stories of Hindu gods and goddesses to teach a lesson on scripture or morality.

Bollywood filmmaking plainly reflects the ancient and deeply ingrained qualities of India’s dramatic storytelling tradition, lending it the ability to reveal the complex beauty of Hindu beliefs and culture. The movies informed my curiosity and spurred me to read Hinduism books and scripture. As a result, it’s all a little less exotic now. Busting into Indian dances is normal and to be expected, and the actors and actresses are as familiar to me as anyone else I love in Hollywood movies. Any jokes or jabs or insults I hear regarding India or its people feels very personal to me now, and it gets more personal every time I eat a new curry recipe or see a new film. It's family now.

Fig.9 SRK was so YOUNG!

When I saw Karan Arjun (1995), starring a very young Shahrukh Khan just before his days as the ginormous and influential star he is now, I was fascinated by the outlandish plot. Karan and Arjun are brothers in a small village who are killed unjustly and their mother prays to the goddess Kali to reincarnate them so they can grow up and come back to avenge their deaths as well as the death or their father by a man jealous of their family’s wealth. They are subsequently reborn and seventeen years later, the brothers visit the village. They are totally unaware of their associations with it, but through some cosmic influence, they soon realize their duty to their mother and their father and set out to kill the man responsible for their original deaths.

That man, who also worships Kali but with decidedly un-kosher evil intentions (Kali looks scary, but she’s actually a loving mother goddess), is portrayed by Amrish Puri, the same actor who plays the Kali-worshipping baddie Mola Ram in Temple of Doom. Until his death in 2005, Amrish was a veteran Bollywood character actor, starring in literally hundreds of films since 1970.

The Möbius strip of pop culture works in mysterious ways.